A Spotter's Guide to Social Product Ventures

How do you know that a software business with a social mission is actually a Social Product Venture? Some might be able to glance at a business and declare “I know it when I see it”, but when dealing with the capital required to hire the best talent to build impactful social good products, we need a more effective and less inscrutable spotter’s guide.

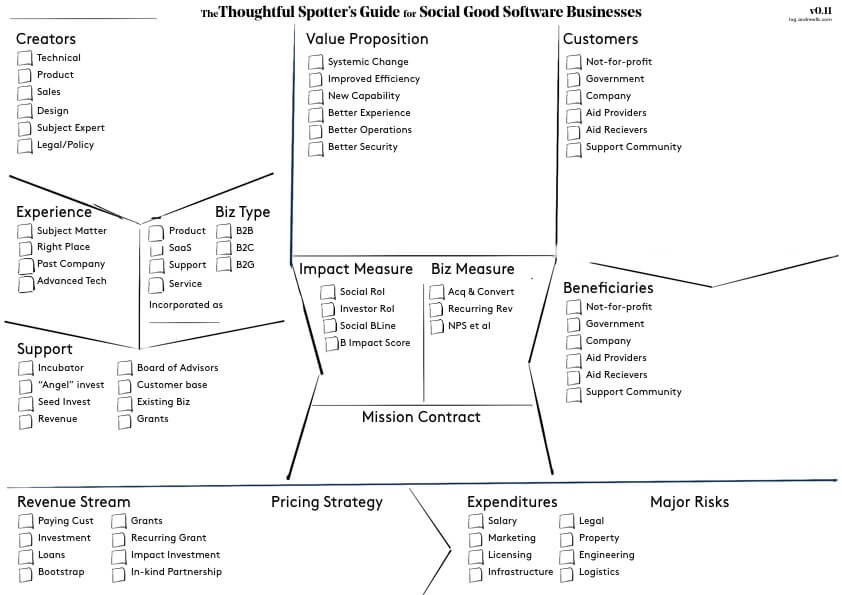

Social Product Ventures exist across a continuum of potential organizational structures: from for-profit businesses with social missions baked-in, to not-for-profits with unique granting structures and partnerships, and everything in-between. Diversity in this way is helpful and good: it creates options and resilience within the social product marketplace. But it creates challenges when it comes to saying concretely “This is a Social Product Venture”, vs. the alternative. If we can’t have a concrete classification like “Delaware C Corp”,“501(c)3 Not for Profit”, “Washington Benefit Corp”, perhaps we can at least have a heuristic for Thoughtful Spotters to navigate the world of social good software businesses.

This guide came from my experience using the Business Model Canvas. The canvas is a tool created by Alex Osterwalder et al. to prototype and explore business models in a rapid fire and concise way. The idea for the spotter’s guide wasn’t as a prototyping tool, but as a tool for classification and understanding. At IDEO, we worked with so many different kinds of businesses and business models, that our head would spin. The Business Model Canvas became an invaluable “Sanity Check” tool, especially when something was unfamiliar or sounded too good to be true. The Business Model Canvas helped us break down what we were seeing, and reveal the familiar and unfamiliar for what it was.

In looking at Social Product Ventures, this Sanity Check has become incredibly important. Many for-profit businesses espouse a social mission or vision for changing the world, but ultimately have nothing organizationally in place to support that mission. Likewise, many not-for-profits talk about technology and product innovation, but have no mechanisms in place to support actual product development and infrastructure. To start making sense of these, I borrowed from the business model canvas and broke down the four verticals that I think are most important:

- Organization (Creators, experience, business type, and support)

- Thesis (Value proposition, metrics, and mission contract)

- Customers (Customers who pay, and Beneficiaries who benefit)

- And Financials in summary (revenue streams, pricing model, expenditures, and key risks)

Each section has a series of checklists with points I keep encountering in my interviews with social product founders. For example, a product team almost always has a Technical person, a Designer, and Product person. In the social venture space, a legal/policy person might also be a subject matter expert, and the Product person is often tied to sales.

Some sections don’t have checklists because they are too diverse, or unique to that market. “Pricing Strategies” could be a checklist if it is a Software-as-a-Service business, but when navigating the relationship between Customer and Beneficiaries, there is often a unique proposition. For example, in the Electronic Health Record space, EHR systems were often priced according to federal funding for “Meaningful Use” dollars, and not market demand per-se.

Organizations is broken down into Creators, Experience, Business Type, and Support.

- Creators are the founding and core team. Where possible, I try to write who is what next to each checkmark, and often early stage businesses will have one person filling multiple roles.

- Experience relates to the founding team’s experience leading into the business. This is often a secret sauce that can hint at the potential for success.

- Biz Type is the type of organization and core model, which is a bit more static and foundational. Where possible, you can also list the type of incorporation.

Thesis relates to the core principal and world view of the business, broken down into the Value Proposition, how that value is measured, and what I’ve called the Mission Contract.

- Value Propositions can be defined in many ways. I’ve laid out a few examples that are common in the social good space, which are often simply improving on existing processes. A “Systemic Change” value proposition might be a Grameen Bank, an “Improved Efficiency” might by a Turbotax-like tool for a terrible bureaucratic system, and a “New Capability” might be Food Stamp balances over text message.

- Metrics are split into Social measures and Business measures. Traditional business measures like Customer Acquisitions and Conversions, various measures of Recurring Revenue, and similar are vital for social good businesses to track. It becomes more challenging with Social Impact measures, such as Social ROI. There are great tools like Sinzer.org that have frameworks for tracking and development these metrics, and I will be developing a tool to help Social Product Ventures explore and define their own success metrics

- The Mission Contract is a key section with a concrete list of things that enshrines and protects the social mission of the business. The might be on the far end of incorporating as a Not-For-Profit or B. Corp, or seeking mission-oriented Venture funding, or establishing an advisory board for community representatives. If this comes up short, you may not be looking at a Social Product Venture.

Customers are the general mix of customers, users, and beneficiaries. I’ve specifically not put User in this category, as that categorization is generally covered in the B2B vs. B2C (vs B2B2C) definitions in “Biz Type”

- Customers are anyone who is paying for the product. This might be a Not-For-Profit, an aid provider like a legal aid clinic, a company like Kickstarter looking to track its B.corp status with a B2B social impact tool, or a user who is a direct aid seeker AND paying for the product somehow.

- Beneficiaries have a mirrored list of check marks, and include anyone who directly (or indirectly) benefits from the venture’s value proposition. This is often someone who is seeking and receiving aid, or a Not-For-Profit that is able to improve its pipeline.

Financials are heavily abstracted, and are mostly a tool to drive more specific questions. They capture Revenue Stream and Pricing Strategy, as well as Expenditures and Major Risks

- Revenue Stream is anything that is bringing in resources with a monetary value (at this point). This can be investment, grants, in-kind partnerships, high-value volunteer hours, etc.

- Pricing Strategy is how the business makes money through its product or service. It might be a yearly licensing fee, it might be tied to a federal funding policy, it might be a per-user usage fee, or a filing fee. Every business has to find the pricing strategy that fits its model and mission, so expect massive variation here.

- Expenditures are the primary drains to your accounts. For software businesses, this is almost always salary and–at-scale–infrastructure. But there might be additional expenditures too, such as licensing, legal fees, property, or logistics.

- Major Risks are the big existential threats. In a highly regulated space, it might be the risk of being in breach or boxed into an ineffective business model. For a not-for-profit serving a smaller community, it might be over-reliance on a single foundation. These are many and should be acknowledged.

By explicitly mapping these factors for software-based businesses with social missions, it enables us to understand, compare, and explore businesses that seem wildly different on their surface, yet carry commonalities in their founding DNA. It allows us to ask the questions that are relevant, and explore the reasons for different decisions with a lens to learn from each business’ unique traits.

So what’s next? This tool is in its very early stages, and will be evolving continuously. I’m actively interviewing social product businesses right now, and have benefited from some great conversations that I’ll be sharing in the coming weeks. These are businesses that are building software products in a dozen different ways, with unique approaches to funding, and with a thoughtful eye for how they can both do good and grow at the same time. If you’re a Social Product Venture and you think you could fill out this Spotter’s Guide, I’d love to hear from you. Drop me a line at lovettbarron@newamerica.org.

(

(