Building the Grant Calculator

What if we made it easier for non-profits to know how much their time was really worth? What if we could surface this true cost of fundraising activities to those engaged in the philanthropic ecosystem? What would the non-profit ecosystem look like if the value of people’s time was measured accurately, and the value of a grant seeking (and making) – a time consuming but vital first step in value delivery for the nonprofit ecosystem – could be considered more objectively by its participants?

We built the Grant Calculator with this idea in mind: to provide a compelling and useful experience for grant seekers and grant makers who want to explore the opportunities presented by the philanthropic landscape, to understand the costs of pursuing funding and the resulting net usable value of those funds, and make better choices for themselves and their beneficiaries.

What is a grant calculator?

The Grant Calculator was co-developed by Dahna Goldstein and myself (Andrew Lovett-Barron), both fellows at New America. Dahna (a technology entrepreneur in the philanthropic sector) and I (a designer previously of IDEO and the US Digital Service) had observed a need presented by grant seekers in the ability to (relatively) objectively consider the value that a grant would bring into their organization, vs. the cost in person hours and opportunity spent in pursuing it. Many non-profit organizations lack staff who can engage in those kinds of financial assessments, and sometimes can’t afford to hire those who can.

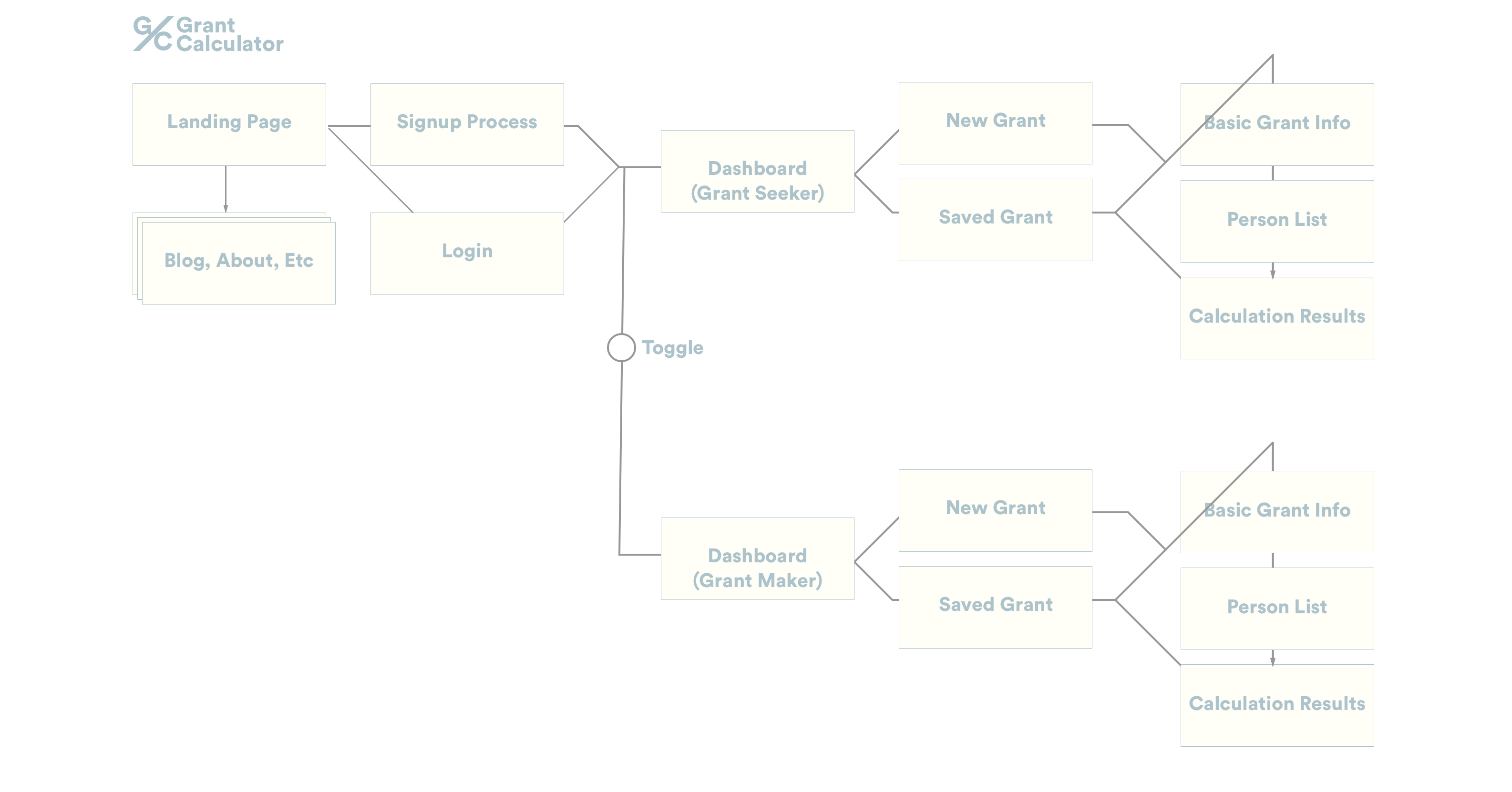

The two groups we considered were grant seekers and grant makers.

Grant Seekers are pursuing grants in order to provide for a particular service, create a new program, hire key staff, etc. They need capital in order to serve the public interest in some way.

Grant Makers are providing philanthropic capital to the non-profit community. They are investing both strategically and sometimes in an on-demand manner, and are central to the delivery of value to communities relying on the services non-profits are providing.

Finally, there is a third group we wanted to consider: those researching and investigating the philanthropic ecosystem. We believe that by developing data-driven insights into how philanthropic capital is allocated and applied, we can create more and better tools for both grant makers and grant seekers to succeed in their missions to serve the public interest.

Planting a Seed

Evolving from back-of-napkin calculations Dahna had created, Grant Calculator evolved over a series of brainstorm sessions, research interviews, design iterations, working prototypes, and eventually software that now is open for use.

We developed the idea through a variety of sketches, and then ultimately a mockup that would become the basis for pitching the tool to the leadership team at New America’s Public Interest Tech program (of which I’m a part) and to PEAK Grantmaking, a nonprofit association dedicated to advancing good grantmaking practices, who helped fund the project.

These crude mockups evolved into a Google Spreadsheets prototype that demoed the initial calculations and some of the core steps in the flow of the application. While visually crude, the tool was an excellent opportunity to test the data fields and language with users, and gut check our own assumptions.

Across a series of user interviews, we tested out the prototype. These users included non-profit CFOs, foundation program managers, and scrappy service providers without a direct account arm. Their feedback and input was invaluable in structuring the application, and iterating on both the language and the flow that went into the beta application, which is currently being used at netgrant.org.

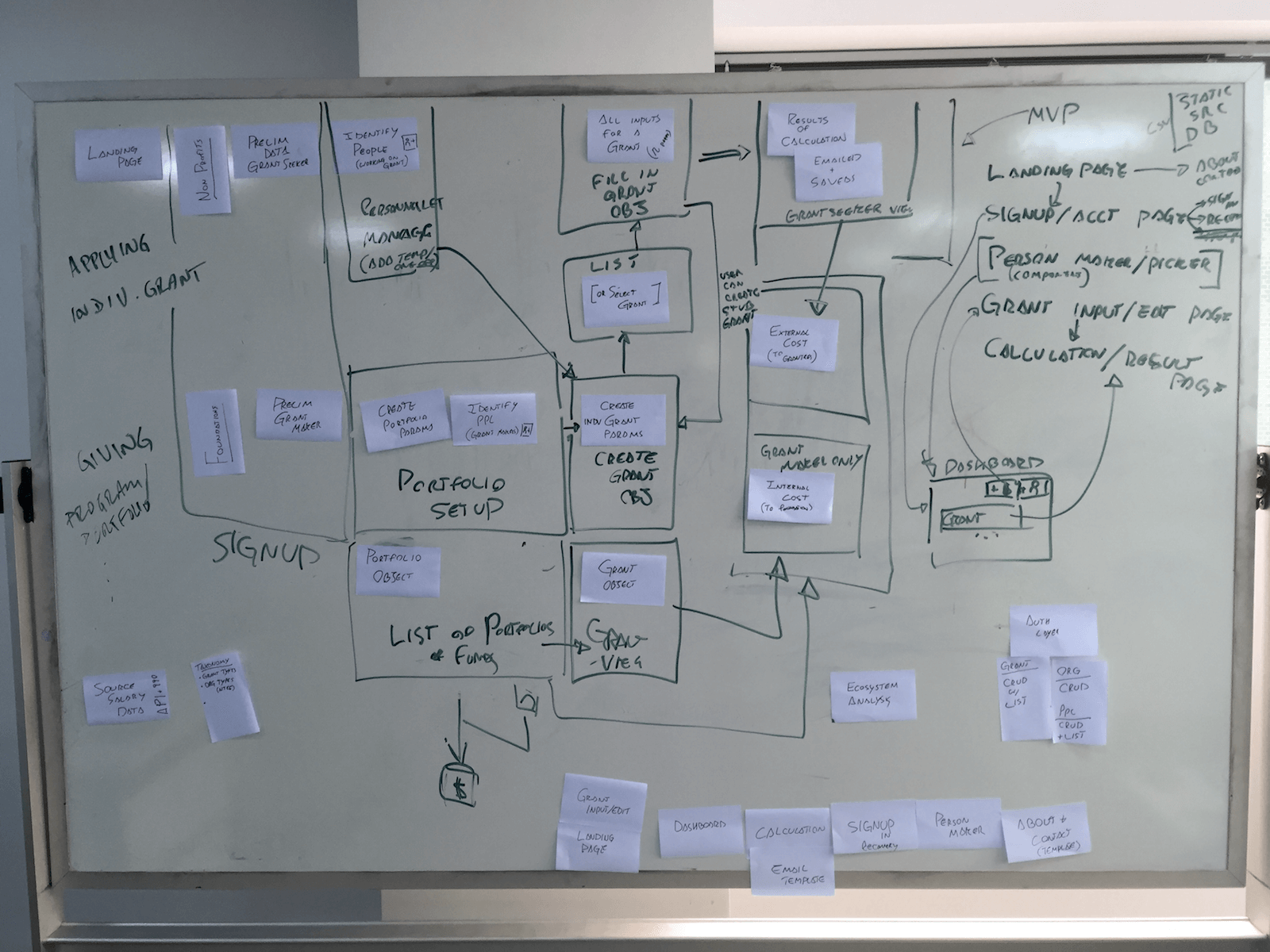

From these interviews, we made modifications to our earlier designs, and sketched out a flow for the application itself.

These structures allowed us to construct a hypothesis about the technical needs of the program, and we got to work putting down the first lines of code.

Technical Structure

The technical side of this tool is a bit of an odd one, and I will try to keep this accessible to the non-tech types with plenty of explanatory links.

It consists of two parts:

The Grant Calculator client, which is a Jekyll blog hosted on Github’s free tier “gh-pages” service. Github pages allows you to host a static open source site, or a jekyll blog as a static site by compiling its output when uploaded. This client has some specific Liquid (the scripting language that Jekyll interprets) pages that render the data input forms from a series of YML (kinda like a JSON, or XML file in that it is structured data) files, as well as a few custom (and substantially reused) backbone (a javascript framework that is a bit outdated, but super stable and easy to use) views that manage the server-side communication and rendering of server responses as data on the page.

The Grant Calculator server is a NodeJS server and a python script. The python script ingests the YML files from the Grant Calculator client’s _data folder, and renders them as node module files that contain Mongoose ORM data schemas. These data schemas are then wired into a simple RESTful API that communicates with the different components of the grant calculator itself.

In the application, three database schemas are created in this way: The User Profile (user passwords and login info are stored separately and encrypted), the Grant Seeker object, and the Grant Maker objection. Each of these is generated from that YML file, and describe all the components of the grant, including hours and contributions, types of grant, and similar.

There are three other data types which are vital to the application:

-

The Person object, basically an individual who has an identifier, a yearly salary, and a title.

-

The title object, which is list of different job titles in the philanthropic sector that includes their mean salary information.

-

The hours object, which is a nested part of the grantseeker/grantmaker objects, and references a person object and their salary, and the amount of time allocated to them for a particular grant.

Combined, these different bits of information allow us to share out the estimated “Net Value” of a grant to both the seeker and the maker in providing it. It also provides a level of user-friendly transparency to grant makers who want to understand how much of the grants value will realistically be utilized by the grant seeking organizations pursuing the grant.

Initially, the decision to render the Grant Calculator client as a jekyll application was for prototyping purposes. I wanted to very quickly get the information from the Spreadsheet into a clickable prototype so we could improve the fidelity of our user tests, and make it easier for our subjects to engage with the prototypes. However, we discovered that it became a fast way for Dahna and I to collaborate on the interface itself.

While not a programmer, Dahna is a tech entrepreneur with a successful exit, and was able to jump in quickly and effectively. It allowed her to take responsibility over the content of the data and its hierarchy in the application while I focused on developing the platform. She would modify and commit changes to the YAML file directly in Github, allowing her to very quickly visualize and test changes to the form data. This also served as a strong template for how future collaborators or “locally hosted” versions of the Grant Calculator might evolve to suit particular organization’s needs, since the form structure can be rapidly changed across the frontend and backend structure.

On the server side, modifications to the YAML files were automated by running the Python script, and then committing the server code to Github. From Github, the hosting platform we were using, Heroku, is able to integrate the changes and restart the server independently. Any changes to the database schema are reflected in future uploads, but otherwise stored normally on the MongoDB server that is hosted on the same platform. It became a simple solution to what would otherwise be a challenge to quick iteration and testing of the concept.

And best of all? By splitting the services across these two platforms, the application is completely free to host, share, and improve upon. We are able to run on Heroku’s free server tier, and host the client application on Github’s GH Pages service.

Building Sustainable Software

Now that we’ve got our beta application up, running, and in the hands of users, we have a different kind of road in front of us.

Maintaining and iterating on software is not the same as building it. It requires different tools, a different temperament, and a different way of considering development. I am the first to admit that I am better at building than I am at maintaining. My last app, Pedal Pedal Club, is a testament to that.

But thankfully we have great support. By working with New America and PEAK Grantmaking on this tool, we not only have great institutions behind us, but also have a community of inspiration and expertise to draw upon. We can maintain and iterate on the tool while asking a number of important questions:

- What features best serve the needs of the grant seeking community?

- How can we provide great tools for grant makers looking to support the philanthropic ecosystem?

- What can we learn from the grants data that might help all actors make better decisions about their time?

- What insights can we draw from the needs of the philanthropic community that might point to new and useful services down the road?

With these questions in mind, the Grant Calculator can become a platform for us to continuously ask new and exciting questions from the community, and to continuously provide new value back. Born in the New America Public Interest Tech program and supported by PEAK Grantmaking, and managed by the Mulligan Fund, we are excited to use it as a platform for considering philanthropic capital in a more human-centric, iterative light.

Grant Calculator –a tool for iteration and thinking– is yours to use and we’re excited to hear any feedback, ideas, or support. Give us a shout at alb@andrewlb.com or goldsteind@newamerica.org